He was making coffee in the kitchen of his grandmother’s summer house, on a late August morning in Sweden many years ago. The sun lay in squares across the wood floor. Through the windows, the lake. I was on the stairs, struck by the quiet beauty of the place — and then struck by a song, scooped up by its notes, cast into its world completely. What is this, I asked, coming up behind him as he poured milk into cups. The Triffids, he replied.

We were deep in the Swedish countryside and we were the only humans alive. Apt conditions for a song called “Bury Me Deep In Love”, except that its overwrought bluster stood so opposite to the tasteful Swedish setting. It sounded a bit like how I imagined Never Let Me Go, the fictional song in Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel, might sound: enormous and soppy — but exploiting 1980s bombast rather than 1950s schmaltz.

There was no internet at the summer house in 2017 so I couldn’t google the Triffids, couldn’t play Bury Me Deep In Love over and over, inspect its magic from every angle. But I thought about the song all day, as we ran through the forest and down to the cold water, and all of the next day, driving back to Malmö, and the day after that, as I paced Copenhagen airport with a cardamom bun in my bag.

I left that wide-eyed Swedish world behind, but I held on to Bury Me Deep In Love. It became my top played song of 2017, a staple on London streets walking to and from university. It is a time capsule of that final autumn term, transporting me straight back to the square carpeted house I shared with friends on Caledonian Road, the shortening days, the olive green jumper and grey scarf I wore all the time back then, Dishoom chai and umber leaves and back-to-school notebooks and walking up Richmond Avenue at sunset.

I listen to it less frequently now, because I am no longer that girl and because I want to hold on to its time capsule power. Certain periods of time contain more life and feeling than they ought to, and certain songs become attached to the potency. Bury Me Deep In Love, with its swooping, overblown production, rose perfectly to the occasion.

There’s no song quite like it. I hadn’t heard of the Triffids before that lakeside morning, only knew John Wyndham’s creepy 1951 sci-fi novel from which the band took their name. The Triffids formed in Perth, Australia in 1978 and burned out by the end of the 1980s. They were sun-kissed goths, fronted by the perfect and doomed David McComb. A guest on a 2007 Australian music documentary optimistically described their best-known song, Wide Open Road, as the equivalent of Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run. Two songs alike only in the way they grasp for an epic sound and feeling, but for Springsteen vast-horizoned escape was something to aim for. For McComb it was something to dread. “The sky was big and empty / my chest filled to explode / I yelled my insides out at the sun / at the wide open road.”

Bury Me Deep In Love followed Wide Open Road a year later, in 1987. It soundtracked the wedding of Harold and Madge on Neighbours. It was rereleased in the UK in 1989 with a B-side cover of Rent by Pet Shop Boys. In 2001, Kylie and Jimmy Little recorded a cover that is anathema to lovers of the original.

The Triffids never quite made it to the big-time but a cult following lives on, particularly in the UK and… Scandinavia. Which explains why I heard a 1980s Australian alt-rock song two months shy of its 30th birthday in the middle of nowhere in Sweden.

I don’t love many other Triffids songs: certainly few from Calenture, the album on which you’ll find Bury Me Deep In Love. Yet the over-production that is Calenture’s main failing is the thing that makes Bury Me Deep In Love great — its motifs, lyrics, and sentiment seem to require that level of grandeur and artifice.

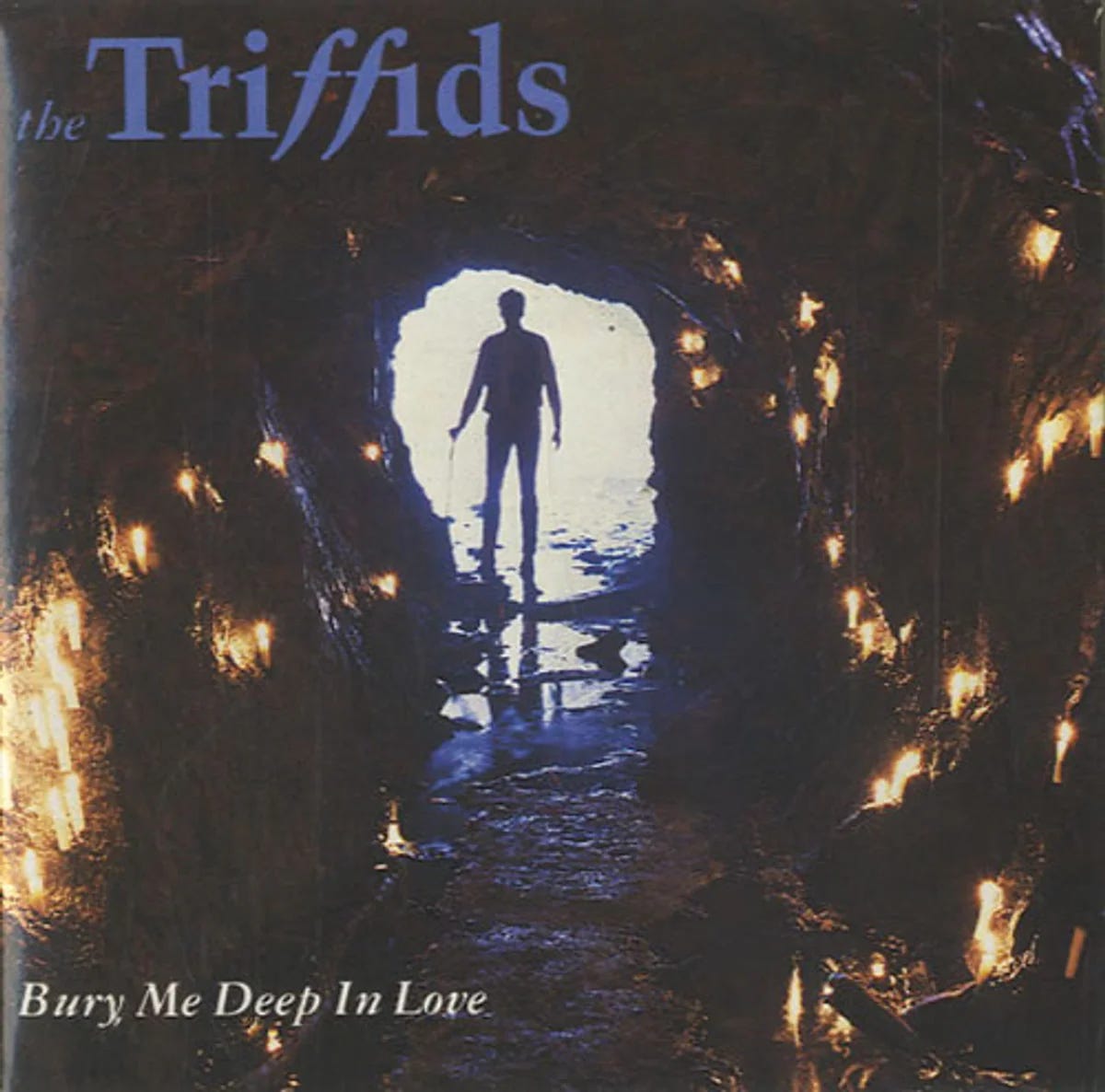

But is the song magic, or is it just an example of the kind of melodrama that locates our innermost vulnerabilities? Is it the striking imagery? The strings? David McComb’s handsome, mournful face? It’s definitely not the music video, filmed in a cave and then amid some awkwardly placed ferns. But when I watched that video again, I felt reassured that my love for the song is defendable. In the now-closed comments section, others felt the same way.

“David, I will never forget knowing you and one thing I remember is you playing me this song for the first time sitting on the floor with an acoustic guitar on your knees in an upstairs room in Lander St., Chippendale, Sydney, c. 1984, with a sheaf of lyrics for other songs-in-progress beside you. My thoughts are with you always.”

“the theater was sold out I was standing in the back of it and I remember the audience was getting forth and back in this overwhelming ambient”

I don’t listen to Bury Me Deep In Love much anymore. But I reach for it on rare days when everything feels calcified, when emotion and life are far-off concepts. When I first heard the song I had no experience of the scale of love and being-aliveness it would teach me about. I didn’t know what it meant to really feel things, and with the line “take him in, under your wing”, to really feel things for another person: the kind of furious, protective, I-would-run-into-a-burning-building-for-you love that is maybe the only thing that makes life worth living. I know now.

There's a chapel deep in a valley

For travelling strangers in distress

It's nestled among the ghosts of the pines

Under the shadow of a precipice

When a lonesome climbing figure

Slips and loses grip

Tumbles into a crevice

To his icy mountain crypt

Bury him deep in love

Bury him deep in love

Take him in, under your wing

Bury him deep in love

When the rock below is shaking

The heart inside is quaking

How long this cold dark night is taking

Bury me deep in love

You may lose me on the east face

You may lose me on the west

I may be covered over in the night

Bury me deep in your love

Kate, what brilliant writing! Thinking of you here in Paris and so honored to have been a part of your ucl trajectory. Fond thoughts j