Halfway through Bruce Springsteen’s show in Dublin last Friday, the boy standing next to me — there alone, about twenty years old and dressed too cool for dad rock — took out his phone to message a friend. “I think this is the best gig I’ve ever been to,” he typed, and I dissolved.

I was twenty years old when I saw my first Springsteen show too, though I would not have called it the best gig I’d ever been to, because it was in London’s Hyde Park, where the view and sound are always bad, and I couldn’t see a thing, and I only knew five songs, and I was hungry. But something about that night must have convinced me, enough to see him play eight more times in the eleven years since.

Eleven years is long enough to have been several different people at his shows: a shapeless pre-university entity, an earnest student, an even more earnest half-adult living in America, and, standing in the Dublin sun on Friday afternoon drinking overpriced white wine from a small plastic bottle, another person altogether — older, no wiser, hopefully less earnest though, with new hair and a career and a different age bracket on online forms.

Springsteen in my thirties is a different beast. Seven years and what feels like just as many lifetimes have passed since I last saw him tour. I don’t need him the same way I did then, in my early twenties, stood at the beginning of an unbuilt life with no tools to hand. Being a Springsteen fan in the 2010s was an urgent grab at identity when my past was rapidly evaporating and my future still felt like a dense fog.

There were people in the Dublin crowd who have been attending Springsteen shows since the 1970s. That’s a lot of past selves to encounter. And Springsteen himself has, of course, been attending Springsteen shows since the 1960s. That’s a lot of past Springsteens to encounter.

In the only song preamble of the night, before a track called Last Man Standing from his 2020 album Letter To You, he talked about joining his first band in 1965 and, fifty years later, finding himself the last surviving member after the death of bandmate George Theiss. “At fifteen it’s all tomorrow and hello, and later there’s a lot more yesterdays and goodbyes,” he said. “But it made me realise how important being present is, being alive in the moment. I always believe that’s why we meet like this.”

A slicker operation than usual governed this particular meeting. Springsteen tends to open these new shows with No Surrender followed by Ghosts, two songs that stand 36 years apart but hold hands in their explorations of mortality, playing in bands, feeling alive. “I listen to that self-consciously over-the-top E Street piano break and think, ‘Damn, he really misses us,’” Rob Sheffield wrote about Ghosts upon its October 2020 release. “Can you imagine the day when we get to sing, ‘I’m alive and I’m out here on my own’ back to him at a show?” I couldn’t. I’d been singing it alone week after week on a grey windswept hill in locked-down London. Yet two and a half years later, there I was, singing it with 20,000 others, Springsteen once again doing his magic trick where he somehow manages to simultaneously collapse and chronicle time.

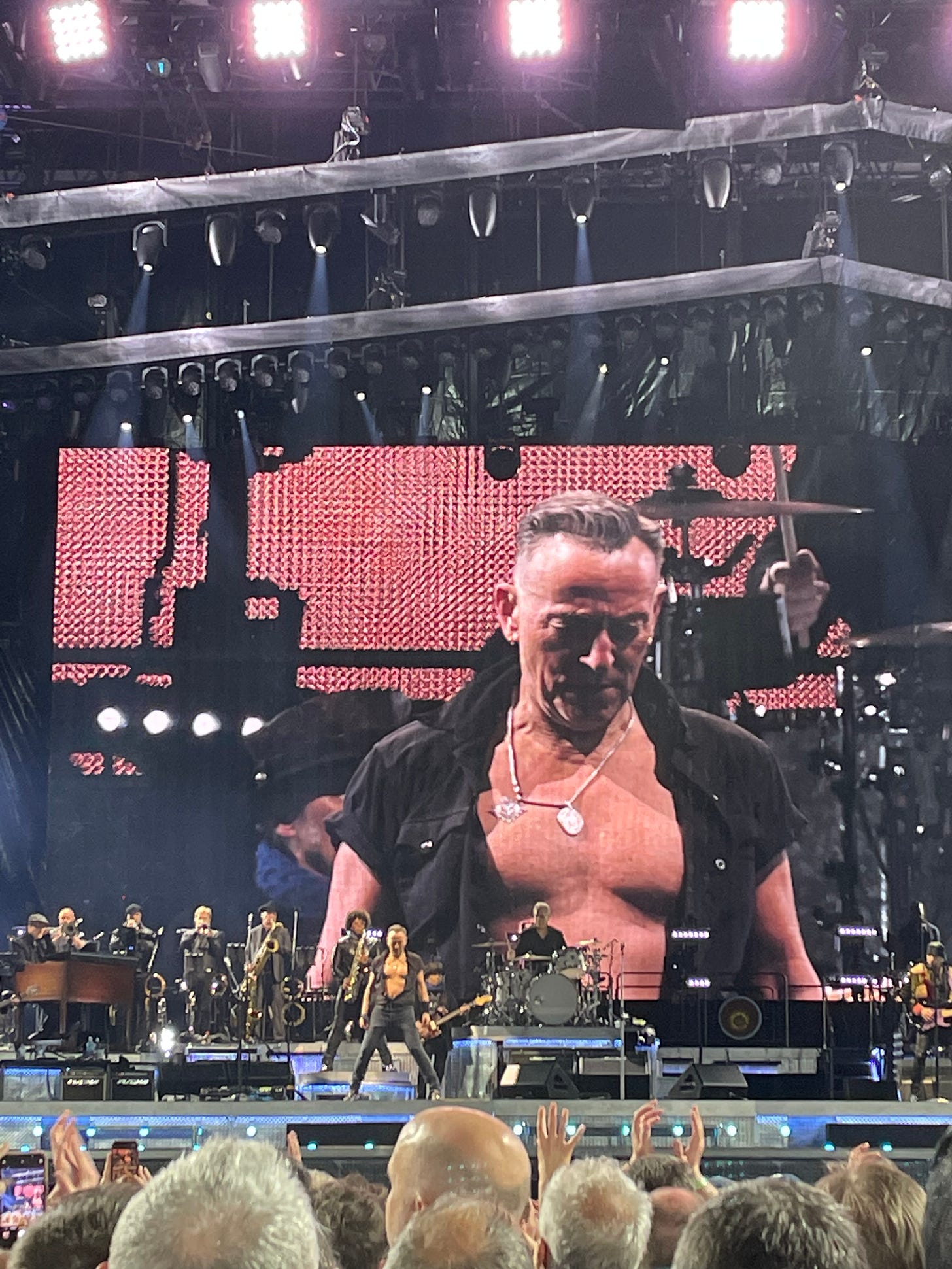

Those two songs introduced the night’s tightly treated theme — mortality — that came accompanied by Springsteen’s daunting athleticism at 73 years old. As he bared his tanned, toned chest to the Dublin crowd with a defiant pop of shirt buttons, it was impossible to fathom that he was the same age as the new British king due to be coronated the following morning.

Pecs or no pecs, though, Springsteen’s getting older, and there were subtle moderations to the previous tour. No crowd-surfing, no signs, no fan hoisted up for Dancing In The Dark, and little chat, presumably to save his voice for the songs. None of this mattered. His shows are by now so honed they’ve developed their own language: Roy Bittan’s piano glissandos, those wide-angled shots of Springsteen looking out to the crowd, the 1-2-3-4s, thousands of hands waggling, Springsteen holding his beat-up Telecaster up in the air — beloved constants that withstand all the time, changes, and seasons.

Still, something tearier replaced the heady joy I felt during his Philly show seven years ago. Every moment in Dublin came tinged with extra emotion, from the sentiments of Commodores’ sad-banger Nightshift — a cover I initially overlooked, put off by Springsteen’s obvious dye job, but fell for with all the live accoutrements (it became the song of the weekend, hummed by fellow fans on the plane home) — to the montage of departed E-Streeters Clarence Clemons and Danny Federici. Obviously no-one was more aware of this emotion than Springsteen himself. “Death’s final and lasting gift to the living is an expanded vision of life itself,” he told us during that aforementioned preamble. At 73, he’s lost a lot of bandmates. Can you imagine how it must feel to sing “you count the names of the missing as you count off time”?

Springsteen’s voice has aged in a way that sometimes spookily conjures the young, whispery self of his first two albums. Seeing him play in 2023, seeing that twenty-year-old boy next to me experience it all for the first time, felt like a similar reconnection with my younger self: acknowledging her while accepting that I am somebody else now too. “I tally my wounds and count the scars, here in the house of a thousand guitars.” Though I don’t listen to him so much these days, Springsteen’s music remains probably the most important of my life, but I think the point of it was to unlock something in me so I could go on and live as many different kinds of lives as possible. And I did, and I am.

In a chipper down the road after the show, an elderly local said, “It’s good to see the old reliables back.” He was talking about the two men behind the fryer, but I agreed with him anyway.

Wonderful, truthful stuff, Kate.